Developing processes for managing standards in Wales

- by Dr Mark Wardle - 8 minutes read - 1621 wordsOur September NHS Wales Technical Standards Board was held on the 27th September.

We have been asked to identify, assess, set and assure technical principles and standards in NHS Wales. That means we need to build a catalogue of standards, including standards that are already in use as well as standards that should be used for new developments. We must recognise a need for pragmatism, so a catalogue must include not only information about that technical standard but how it should be implemented and used.

In this meeting, we discussed how to build safe, reliable, functioning processes to assess a technical standard for use within NHS Wales. It is important to recognise that this blog post is a snapshot of my reflections. As a board with an explicit adopted principle to be open and transparent and adopt an iterative approach to our work, fostering a culture of continuous improvement, these notes are simply that: notes and a work-in-progress.

With that caveat, what broad range of issues did we discuss?

Things to consider

For any standard, we discussed a range of factors that might need to be teased out during any open, transparent process we wanted to design:

- what is the user need? what are the use-cases?

- is the standard already used?

- is the standard already deprecated?

- are others using, working on or interested in this standard already?

- what can we learn from others using or working in domain in which the standard operates, and how do we engage with others who are using, working on or interested in this domain?

- is the scope of the functional requirements correct, or does it need to be broadened or made more specific?

- is the standard supported or due to be supported by the market? do we need to explore the market?

- what scoring mechanisms (e.g. procurement) can we use to discourage the use of standards at their end-of-life, and likewise, what can we do to drive market adoption?

- what are the false barriers to entry?

- what are the lifecycle issues to consider? (draft, draft-for-use, standard, deprecated but still in use, deprecated and not for use, planned?)

- how does one identify or drive traction of a standard?

- how do we judge the need and the content of a standard, particularly for new developments?

Architecture and interoperability

When we think of technical standards, we thought it helpful to consider the different places in which those standards might be used for interoperability. Interoperability is how we make make computer systems or software exchange information. Most of us recognise that simply exchanging information is insufficient but instead we must aim for meaningful (semantic) interoperability in which systems exchange information and make use of that information.

Almost all computer systems try to break down complex problems into discrete modular components, each of which do a limited set of things very well and traditional applications stitches these together into what appears to be a cohesive whole. Modularity means that teams can work semi-independently of one another and so long as they interact appropriately (at technical, legal and human levels).

Interoperability is usually used to define the interactions between distributed systems and software. This enables technologies such as the World Wide Web, in which your computer has no difficulty in interacting with software running on a completely different computer somewhere else in the world to show you a web page.

We already use interoperability in healthcare as almost all health enterprises use a range of computer systems that need to be made to work together. A common, if old-fashioned example, is the use of HL7v2 to send messages regarding admissions, discharges and transfers. As a source system notifies dependent systems about a change by sending a message, we call this approach push messaging.

Push messaging is well established within health enterprises and most have adopted a messaging fabric that acts as a safe bus to transport messages across systems with high levels of scalability, monitoring and queuing as well as often providing assertions as to reliability and performance. But there are problems with it. Dependent systems need to potentially deal with a constant influx of messages being sent to them and managing security is difficult. A source system sends out messages and therefore controlling which subscribed systems should be notified can prove challenging; many push enterprises adopt a patient-of-interest list that defines a subset of patients for whom a target system should receive messages. Inherent in this architectural design, is the concept that each application maintains its own state, with messages being used to keep disparate disconnected systems consistent.

Instead, modern enterprises have moved towards a model of “pull messaging”, in which a system retrieves data from another and we decouple software logic from data so that many applications and services become stateless. This means that security checks become much easier because we can understand, at the time of the request to retrieve that data, which application is making the request on behalf of which user.

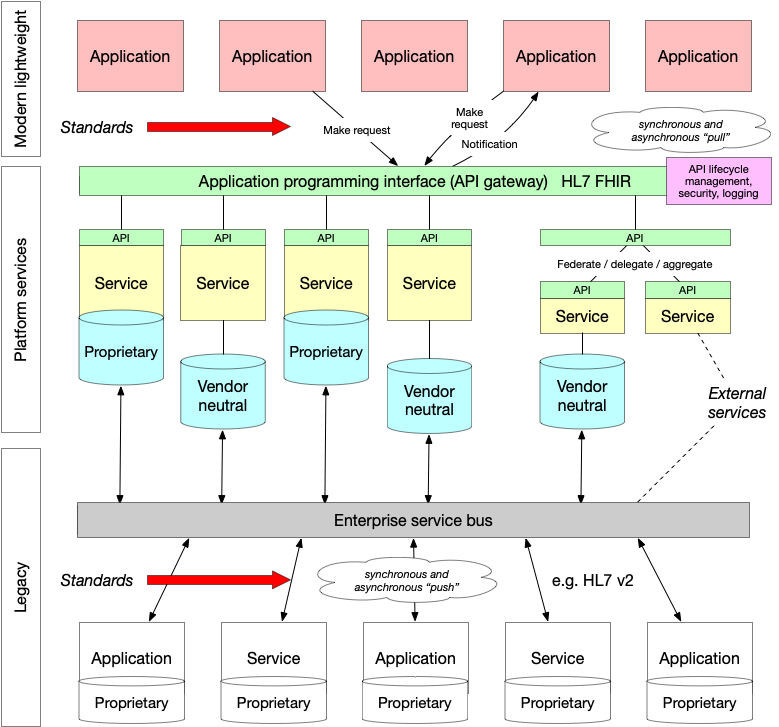

I sketched a version of this schematic in order to try to understand the use cases and the difference between a “pull” and “push” approach.

For example, a laboratory test result is pushed from a laboratory information management service (LIMS) and is stored in a vendor-neutral archive. In Wales, we call this the Welsh Results Reporting Service (WRRS). We could expose that archive as a FHIR diagnostic report https://www.hl7.org/fhir/diagnosticreport.html as a microservice. Multiple independent services like that are blended together into a cohesive whole to create what appears to be an enterprise-wide cohesive API acting as a gateway and hiding (abstracting) the underlying implementation. Importantly, if we wanted to show laboratory results from other centres, we could either use one of two approaches to provide a unified view:

- a federate/delegate/aggregate model, in which a service accepts a request for data, sends that request to multiple other private services, collects the responses to create a unified view

- a shared repository model, in which all centres push data into a shared repository via health information exchange.

This approach to architecture means that, while we have a LIMS that does not support HL7 FHIR and appropriate UK-wide shared profiles, we can still expose our laboratory data via HL7 FHIR. Once LIMS is replaced by a version that natively supports the more modern technical standards, we can deploy and existing modern applications do not need to be modified in order to continue to run.

The important considerations are:

- use of vendor neutral data repositories

- move towards an application programming interface (API) approach built on open standards

- understand that need to liberate data from legacy applications and make use of existing infrastructure

- existing legacy includes tightly-coupled bespoke integrations that do not fit into this schematic. Such an approach needs to be deprecated in favour of a more modular loosely coupled architecture

As such, we surely need to consider technical standards at multiple levels of our architecture, taking into account existing infrastructure and a clear future direction. This is shown graphically with the arrows.

I believe that the future of electronic health records is based on:

- open standards

- distributed systems

- lightweight applications

- shared common services for data and logic

- domain-driven modelling for clinical and administrative data, as well as clinical workflow

Process

So given these considerations, how can we define a process that we can use in order to make rapid, pragmatic process while keeping within the broad principles and cohesive, credible technical architecture for our health and care data?

We worked through an example request for a standard - one of our colleagues from Aneurin Bevan submitted a request for a “Technical standard to support exchange of eObservations information using HL7 version 2 (HL7v2) messages”.

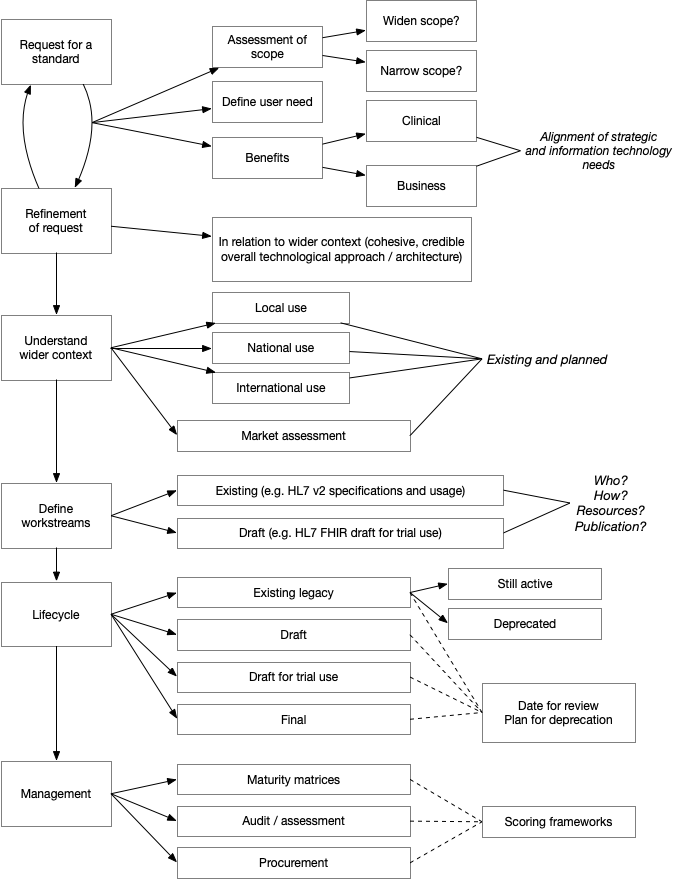

This was a really useful example, and it led to a draft standards assessment process which I have drawn out here:

One of the important considerations is to ensure the scope is defined, particularly in relation to high level clinical requirements - user need. Understanding the alignment between information technology and our wider strategic objectives is critical. For this technical standard, we need to understand why we are being asked to help with eObservations and put that in context of our wider architectural and technical infrastructure plans.

It was immediately clear that there was uncertainty about the scope of this request, as it specifically requested an NHS Wales standard on the format of HL7 v2 messages. In my view, we must broaden the scope to understand the wider clinical need, perhaps in terms of user stories, to see that what we are trying to solve is not simply exchanging HL7v2 messages but providing a wider framework for handling and making use of eObservation data. As a result, this request could be broadened to include technical standards for HL7 FHIR resources representing those data as well as HL7v2 messages that are sent by applications and services that do not, as yet, support HL7 FHIR.

Our plan now is to draft a more broad eObservations technical standards paper to include some of the factors outlined in my process diagram to see whether the process works and is helpful. I will write another blog post when we have learnt more about this!

Finally, I would like to re-iterate the importance of a learning culture in our work: we adopted the GDS design principles. One of those is the use of iteration and incremental improvement. While you might consider such an agile approach for our software development processes, I would argue that we also need to approach our wider technological leadership and management approaches in an agile way; that means we test our assumptions and make incremental improvements to the way we work. This post is my attempt to embrace that approach. Let me know what you think.

Mark