Modelling medications

- by Dr Mark Wardle - 21 minutes read - 4310 words“When we set out to write software, we never know enough. Knowledge on the project is fragmented, scattered among many people and documents, and it’s mixed with other information so that we don’t even know which bits of knowledge we really need. Domains that seem less technically daunting can be deceiving: we don’t realize how much we don’t know. This ignorance leads us to make false assumptions.”

Excerpt From: Eric Evans. “Domain-Driven Design: Tackling Complexity in the Heart of Software”. https://www.amazon.co.uk/Domain-Driven-Design-Tackling-Complexity-Software/dp/0321125215

I first need to say a big thank-you to the members of the WTSB for their input today . We had very useful discussions and I think we all learned a lot. This blog post reflect my personal notes and thoughts from the meeting; we will, of course, make more formal minutes of the discussion public once available.

Medicines : what problems are we trying to solve?

From a personal point-of-view, prescribing is one of the most dangerous things I do, and as a full-time clinician working in a hospital setting, I currently have few tools or technology to help me work efficiently and safely.

So what kinds of work do we need to consider?

- writing prescriptions

- managing and ordering stock

- tracking administration of drugs, as required or as-scheduled.

- tracking medications used for clinical decision support, helping us solve the “tell me who is taking methotrexate?” problem

- sharing and exchange of information between care boundaries and better support of those processes

- understanding our interventions better, such as post-marketing surveillance, by combining medication data with other data such as outcomes

The problems we face are:

- most hospital doctors in Wales have no support for e-prescribing, so we prescribe on paper.

- medicines information either doesn’t exist in digital form, or exists in multiple systems and yet clearly impacts many different workflows, many of which are not digitised either.

- there is no single ‘source of truth’ for “current” and “past” medications taken by a patient

- medication reconciliation between different systems frequently requires manual re-entry, even if both systems are digital, although often we would acknowledge checks when patients cross boundaries of care are usually appropriate (e.g. when a patient is admitted, we might stop the ACE inhibitor while they are dehydrated and septic - the actual need to re-enter or review each drug is a valuable opportunity to reflect on whether it should be continued).

But digitisation of any process or workflow is not a panacea; we need to ensure that a complex intervention like this is an opportunity for learning - to study our efforts across different care environments and ensure what we do, at the technology level, is safe and effective. You might ask, isn’t there already evidence like that? Not much, and historically healthcare information technology has been poor at rigorous evaluation and ongoing monitoring. For example, there are few robust evaluations of the advantages and disadvantages of e-prescribing and few “lessons learnt” open transparent discussions of the problems faced and the solutions used to overcome those issues.

So, where are we in Wales so far?

WHEPPMA

We welcomed Cheryl Way, national pharmacy and medicines management lead, to discuss technical standards relating to medicines.

She presented on behalf of the NHS Wales’ WHEPPMA team, Welsh Hospital Electronic Prescribing Pharmacy and Medicines Administration project who are working on delivering the benefits of technology in prescribing and medicines management in Wales.

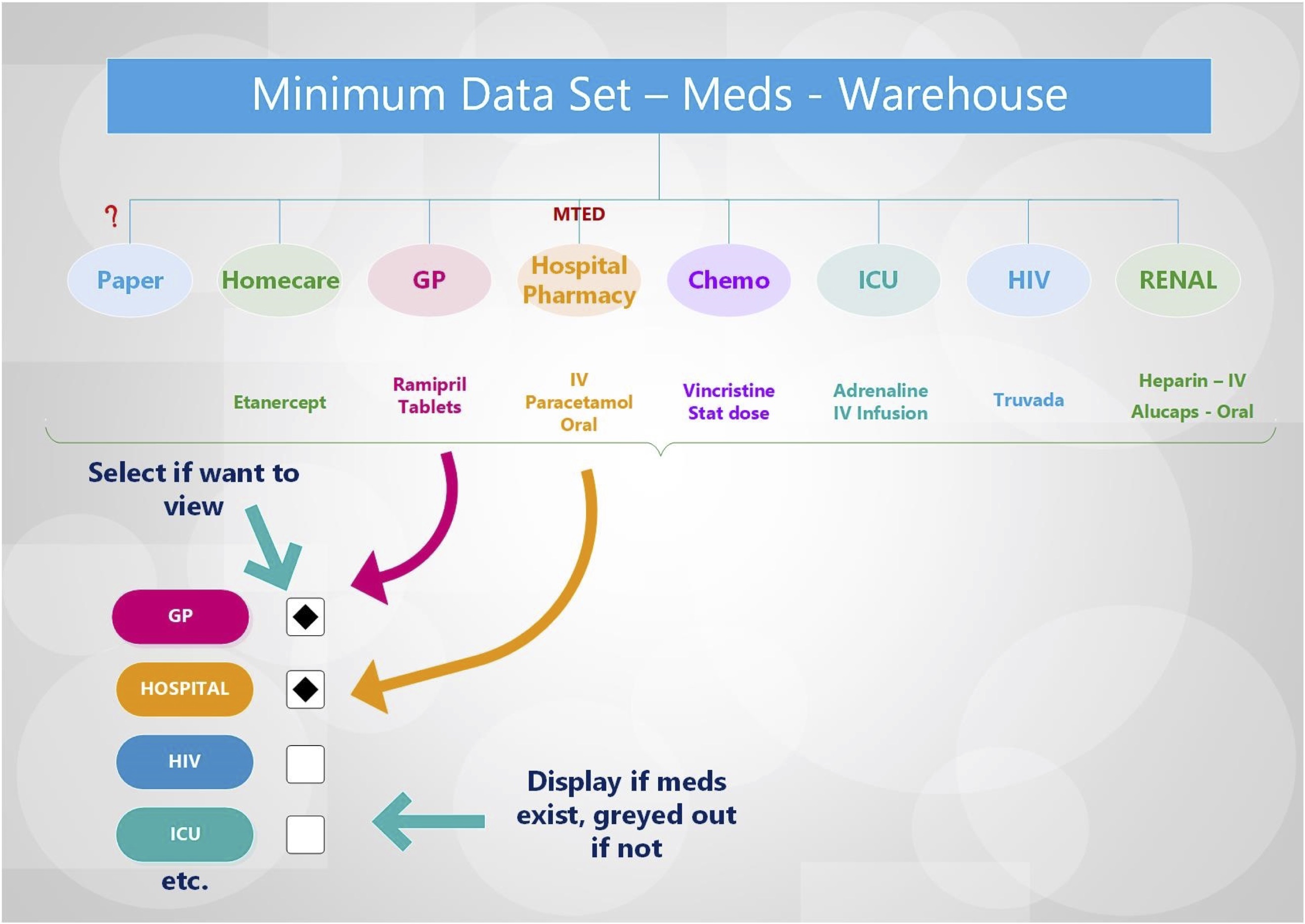

This is their schematic representing the complexity of taking information about medicines and their management from multiple sources in order to help a user, whether patient or professional, understand what medications have been prescribed (and perhaps taken) by a patient:

Medicines reconciliation across systems. Courtesy of the WHEPPMA team.

What the schematic demonstrates well is that data relating to medicines currently exists in multiple software systems, such as medication records from general practice, the hospital pharmacy, and specialist prescribing such as chemotherapy. For example, I regularly issue outpatient prescriptions for drugs such as mycophenolate but that information is likely to be missing from the general practitioner record unless someone reads my letter and records that information manually!

However, it is important not to misinterpret this schematic; it shows how a user might combine a list of medications from multiple sources in the context of direct care for an individual patient, but clearly, we need much more than that. Showing a list to an end-user is but one of our use-cases. We need to ensure that our medicines problems are framed correctly, because we risk making the wrong decisions if all we ask for is a view of data across different systems. It’s akin to driving into a cul-de-sac when we need to get somewhere else.

“Other projects use an iterative process, but they fail to build up knowledge because they don’t abstract. Developers get the experts to describe a desired feature and then they go build it. They show the experts the result and ask what to do next. If the programmers practice refactoring, they can keep the software clean enough to continue extending it, but if programmers are not interested in the domain, they learn only what the application should do, not the principles behind it. Useful software can be built that way, but the project will never arrive at a point where powerful new features unfold as corollaries to older features.”

Excerpt From: Eric Evans. “Domain-Driven Design: Tackling Complexity in the Heart of Software”. https://www.amazon.co.uk/Domain-Driven-Design-Tackling-Complexity-Software/dp/0321125215

We need to truly understand our domain, and build a model of that domain - focused on its building blocks and underlying principles. That means understanding data and the workflows that operate using those data.

Towards structured, meaningful data

As such, we must be careful not to build solutions that seemingly solve an immediate problem without a deep understanding of the domain. For example, we might simply create a solution to bring medicines together for display purposes but take us no further towards solving more ambitious problems such as clinical decision support that could, for example, highlight neutropenia in a patient with fever who has received recent chemotherapy.

“The heart of software is its ability to solve domain-related problems for its user. All other features, vital though they may be, support this basic purpose. When the domain is complex, this is a difficult task, calling for the concentrated effort of talented and skilled people. Developers have to steep themselves in the domain to build up knowledge of the business. They must hone their modeling skills and master domain design.”

Excerpt From: Eric Evans. “Domain-Driven Design: Tackling Complexity in the Heart of Software”. https://www.amazon.co.uk/Domain-Driven-Design-Tackling-Complexity-Software/dp/0321125215

Part of the solution is to create a shared information model; a model is representation of the real-world. All models are wrong, but some are useful and if different systems share those models then they can exchange information; we achieve semantic interoperability.

Creating information models

We already have widely-used standards for medications - the UK dm+d, a dictionary of medicines and devices that is also available as a part of SNOMED CT. Using the dm+d, we can understand medicines, the ingredients that make up those medicines and the products available. In the USA, they use RxNorm.

However, simply recording a code from the dm+d (or RxNorm) is insufficient. What is the use of a list of medicines in isolation? In a paper record, how much use is a list of medications unless it is contextualised?

How would we interpret a list of medications without any other information? Is it a list of medications:

- currently taken by the patient?

- prescribed for the patient?

- ones to be stopped at this encounter?

- ones to be started?

and what about additional information such as:

- dose?

- timing?

- instructions on changes in any of these over time?

- the prescriber and the responsible clinician?

- the situational context of the instruction/administration?

Our models relating to medication need to include all of this contextual information and carefully consider the workflows relating to medications, such as prescriptions (an order/request), how professionals patient or carers might record administration, how organisations (and individuals) manage stock ordering and control. In addition, we need to carefully consider the different clinical environments in which they are used such; are there significant differences between a general practitioner prescribing a week’s course of an antibiotic, an infusion prescribed on the intensive care unit, or a chemotherapeutic agent prescribed as part of a wider protocol?

“The key to controlling complexity is a good domain model, a model that goes beyond a surface vision of a domain by introducing an underlying structure, which gives the software developers the leverage they need. A good domain model can be incredibly valuable, but it’s not something that’s easy to make. Few people can do it well, and it’s very hard to teach.”

Martin Fowler, excerpt from preface in Eric Evans’ “Domain-Driven Design: Tackling Complexity in the Heart of Software”. https://www.amazon.co.uk/Domain-Driven-Design-Tackling-Complexity-Software/dp/0321125215

The seductive single system solution (SSSS)

It is easy, when faced with this complexity, to think we can solve our problems by buying a ‘single system’ and making it available in all clinical contexts, perhaps by embedding a view of that system from another in a rectangle on the screen. Indeed, perhaps such as approach helps to standardise the user interface which might have important patient safety benefits? Perhaps, but:

we will never have a single ‘system’; we will always need to exchange data between software across our complex enterprises

- e.g. how could that possibly work for patient/carer facing applications, e.g. epilepsy drug reminder applications?

- e.g. who is to say that the best way of prescribing drugs on the ward is the same as prescribing chemotherapy regimens? Isn’t some variation appropriate?

we do not yet know the best way to valuably use technology to improve our work here. We only need to consider the widely discussed ‘alert fatigue’ to recognise the importance of ensuring that we use technology to build a learning culture of continuous improvement.

we need to be very cautious unless this is this a ‘solved problem’, for which the answers are well-understood, and the market providing solutions which have become commodities and essentially substitutable.

do we really think that medications can be handled by a standalone application on behalf of all others? How are we going to add analytics and integration with other sources of information (e.g how do we solve “send an alert if there if there is a problem with blood monitoring results for patients on methotrexate”)

in short, are we going to impede innovation and ongoing improvement?

And what about the purported benefits to safety and training?

- we can mitigate these issues by defining standards for display and workflow relating to drugs (e.g. show full names and no abbreviations for dose timings) without impeding innovation (and recognise that design is likely to be quite different for small mobile devices compared to a desktop display).

The biggest issue with the ‘seductive single system solution’ is that embedding another application, with its own user interface, business logic, data models and storage, results in a potential combinatorial explosion of different systems which need to be integrated point-to-point to support processes and workflow.

Simplifying complexity

The answer is, I think, to simplify and break down our work.

We need:

- a deep understanding of the problems we want to solve, now and in the near future

- to build models - think in terms of meaningful structured data and the operations/processes that use them, and explicitly model state, making other data stateless and immutable. Turning implicit tacit knowledge into explicit models is vital.

- to work to sound architectural principles, separating our enterprise into dependent but separate tiers relating to

- user interface

- application layer

- domain layer (our domain models and business rules)

- infrastructure layer

“A model is an abstraction of the real-world distilling knowledge into core concepts and processes. A model is a careful balance between complexity and over-simplification with models that are too complex providing brittle abstractions which are poorly generalisable and models that are too simple not supporting all of the demands placed upon it in real-life clinical scenarios.”

Mark Wardle, “Towards a domain-driven, model-based approach to developing clinical information systems: innovating for the future in NHS Wales”, February 2017

In essence, we are looking for ‘goldilocks models’, not too complex (brittle), not too simple (not useful).

The key results from this approach are:

- loose-coupling between components across the enterprise, permitting those components to be developed semi-independently and in parallel, improving productivity and efficiency and fostering innovation when appropriate.

- a need for shared, coherent information models.

- a move from tacit implicit rules to explicit declaration; we gain understanding of our domain.

Loose-coupling works because the teams agree a set of technical and operational contracts (usually application programming interfaces) so that each party understands both their obligations and entitlements from other parties.

We achieve exponential gains in productivity if we open up those contracts to multiple parties, via the use of open published standards. In this way, we define the technical standards that permit the exchange of meaningful information and ensure that the parties do not necessarily need to engage directly with each other; operate according to the standards and your team can make use of work from another without constant interactions between those teams.

Without standards, parties must engage directly with one another resulting in a combinatorial explosion and a brittle, difficult to change architecture.

An example of the use of standards to connect disparate software is the operation of your web browser. The developers of that browser do not know the people who created the individual websites with which you interact, but instead, because of open standards, their software can exchange meaningful information with the software running on the server.

Information models for medication

So we can see that an information model for a medication might need to include:

- the medication - coded so that, for example, we can determine the class of drug - and determine that amlodipine is a calcium channel blocker

- the dose

- the dosing schedule (e.g. three-times-daily)

- the route of administration

- duration for which the drug should be used

- other dispensing information - e.g. drug is intended to be used forever, but we’re going to supply for next three months.

- a record of the drug’s administration, particularly in hospital and care home settings but an absence of this information does not necessarily mean the drug was not given in other care settings such as the patient’s home. In that situation, other information relating to whether drugs are taken, occasionally missed or not taken might need to be recorded in the record.

It’s important to understand the situations in which information models containing this kind of information might be used. To do that, it might be helpful to consider the admission of a patient into hospital as an emergency and how a record of a drug and other relevant information might be needed.

Where might we need to record or find information about medication?

- A statement - the medication list as told/recorded

- An order - prescribing medications

- Dispensing - providing medications

- Administration - giving medications

Medication statement

We will need a statement of the medications taken by a patient at a snapshot in time. For example, we might ascertain a list when we first meet a patient. Such a step will always be needed, even in the unlikely event that all professionals involved in the care of that patient use the same electronic system, in case the patient has discontinued a drug or started a new over-the-counter remedy.

That’s not to say that software cannot help this important reconciliation and review step; a list of medications could be presented for review sourced from all authoritative sources in order to improve safety and efficiency.

An order - prescribing medications

We need to be able to request medication; a medication order, in which a prescriber orders medication for a patient. This is akin to prescribing on a paper chart, after writing down the list of medications during the process of admitting a patient to hospital. So which list should be the authoritative source of medications that should be prescribed? Once we have decided what to prescribe, those drugs need to be prescribed and those instructions need to be recorded in an appropriate information model.

Dispensing - providing medications

When a medication is prescribed on a ward, a complex set of processes begin. Is the drug stocked on the ward? Does it need to be ordered from pharmacy? Has the patient brought in their own medication? Such information needs to handle the dispensing of the medication to the appropriate location, linking with stock ordering and control systems.

Administration - giving medications

When a medication is given by a professional to a patient, such as an intravenous infusion, that process also needs to be recorded appropriately, or a reason for its non-administration recorded.

Process / workflow models for medication

In essence, the medication statement is akin to the list of medications written down on paper during a hospital admission. When using paper, lists of medications might appear in a letter from the primary care physician, and in numerous duplicate places during admission and subsequent assessment; by nursing, medical staff as well as documents recorded by allied health professionals. At the moment, a single piece of paper cannot be in more than two places at the same time, so that means duplication and redundancy. Which is the ‘truth’? The record by the doctor or the nurse in the emergency department, the ward nurse, or the specialist doctor, or none of the above?

From an informatics point-of-view, the inherent implicit redundancy is fascinating, particularly when we consider how to digitise the process. In effect, digitisation should force us to start to unpick and understand our processes, breaking them into their core steps and allowing us to re-imagine those processes given the tools we now have available to us.

To be successful, we need to:

- make tacit, implicit rules explicit

- handle the contradictions and oddities that have evolved in our ‘systems’

and recognise that many of our tacit rules and oddities have arisen as a result of the strengths and limitations inherent in our use of paper.

We can see, even with a very simple analysis, how we use, manage, record and process medications for patients is complex.

Many of the workflows are quite standardised between different care environments, but others are highly variable. It is useful to consider the ‘edge-cases’; in healthcare, edge-cases are common.

Consider the differences between the following clinical environments:

- prescribing and administration on the intensive care unit vs. nursing home resident

- chemotherapy prescribing vs. regular repeated medication prescriptions for long-term health conditions

- emergency unit prescribing vs. a palliative care plan

“It is with this move beyond entities and values that knowledge crunching can get intense, because there may be actual inconsistency among business rules. Domain experts are usually not aware of how complex their mental processes are as, in the course of their work, they navigate all these rules, reconcile contradictions, and fill in gaps with common sense. Software can’t do this. It is through knowledge crunching in close collaboration with software experts that the rules are clarified, fleshed out, reconciled, or placed out of scope.”

Excerpt From: Eric Evans. “Domain-Driven Design: Tackling Complexity in the Heart of Software”. https://www.amazon.co.uk/Domain-Driven-Design-Tackling-Complexity-Software/dp/0321125215

What standards already exist?

HL7 FHIR supports a range of information models for medication:

- A medication statement.

- A medication request (order)

- A provision/supply of a medication - a medication ‘dispense’

- A medication administration

“The philosophy behind FHIR is to build a base set of resources that, either by themselves or when combined, satisfy the majority of common use cases. FHIR resources aim to define the information contents and structure for the core information set that is shared by most implementations. There is a built-in extension mechanism to cover the remaining content as needed.”

openEHR also provides a wide range of models for medication.

- A medication summary (essentially a statement as above)

- A medication request (order)

- Medication management archetype

- Medication supply

- Medication summary

- A medication item

- A medication list

openEHR defines a core reference model into which archetypes, user-defined information models, can exist in different contexts. For interoperability, distributed computer software must use the same archetype definitions, and there are collaboration tools available that support that process.

My view is that we must, as a community, work to standardise our approach to information models and the reference model in which they sit. In the majority of cases, the hard work is that collaborative, human work rather than the technical factors. I don’t really care how those data are persisted, but only that I can make use of those data.

Computability

What is the point of recording information unless we can make use of it?

That means structuring information so that we can build software to support workflow and process relating to medication; that means software gaining understanding of what data means.

In my opinion, it is easier to write software that processes data as a FHIR resource because it is mostly explicit and developer-orientated. While I love the two-level modelling paradigm in openEHR, software cannot always simply handle archetypes in a generic way. The openEHR architectural review recognises this issue:

“Clearly applications cannot always be totally generic (although many data capture and viewing applications are); decision support, administrative, scheduling and many other applications still require custom engineering. However, all such applications can now rely on an archetype- and template driven computing platform. A key result of this approach is that archetypes now constitute a technology- independent, single-source expression of domain semantics, used to drive database schemas, software logic, GUI screen definitions, message schemas and all other technical expressions of the semantics.”

There are ways of handling these issues, but both openEHR and HL7 FHIR can also make computability more difficult by being too flexible on their use of coding and ontology. That means that both usually fail to specify explicitly which coding system to use, recognising the need for flexibility in usage across territories and environments. Both bind terminologies in a flexible manner.

From the openEHR medication archetype:

NAME: The name of the medication or medication component.

Comment: For example: ‘Zinacef 750 mg powder’ or ‘cefuroxim’. This item should be coded if possible, using for example, RxNorm, DM+D, Australian Medicines Terminology or FEST. Usage of this element will vary according to context of use. This element may be omitted where the name of the medication is recorded in the parent INSTRUCTION or ACTION archetype, and this archetype is only used to record that the form must be or was ‘liquid’.

From the HL7 FHIR medication model:

Medication.code

Definition: A code (or set of codes) that specify this medication, or a textual description if no code is available. Usage note: This could be a standard medication code such as a code from RxNorm, SNOMED CT, IDMP etc. It could also be a national or local formulary code, optionally with translations to other code systems.

https://www.hl7.org/fhir/medication-definitions.html#Medication.code

This flexibility is both a strength and a weakness. In order to be interoperable, we need to be opinionated on how such terms are coded. I will not be able to exchange meaningful information with you, and use that information for computation, if I expect SNOMED CT dm+d codes and you expect RxNorm, even if we both use HL7 FHIR.

Profiling

The suggested solution is profiling; this is a process in which a generic model from the platform standard is adapted to specific use-cases. For example, the UK INTEROpen project has profiled medications so that medication code must be a SNOMED CT code from the dm+d, which is appropriate the UK audience.

The problem with profiling is that we still need to agree across borders how we will adapt our models for local implementation, and this applies to both HL7 FHIR and openEHR. That means building in cooperation and collaboration - across all organisations in health and care, inside and outside, of Wales. We must align those profiles with our partner organisations in order to appropriately exchange meaningful information relating to medication and manage workflows across organisational boundaries.

Conclusions

- we need a deep understanding of our domain and the workflows/processes that are involved in medications

- in general, the technical aspects are not the difficult bit - and there is considerable alignment between models in HL7 FHIR and openEHR already.

- technical standards are not something that can be defined separately to the business of solving problems; indeed, standards are a key foundation in empowering cultural change and digital transformation, and that is everyone’s business.

- work on technical standards must be done in partnership and collaboration, across health and care, involving internal and external stakeholders, inside and outside of Wales.

- we need to build links with our partners and create a learning culture.

- our adoption of technical standards will need continual work and ongoing maintenance and review.

And specifically in Wales,

- we must ensure appropriate technical standards are mandated for new information systems dealing with medications and their management; the WHEPPMA project should be explicit in adopting a standards-based approach.

- we must provide a strong steer to our industry partners that we are moving to a non-proprietary open standards-based approach to medications (and health and care information systems in general)

- we must work with colleagues in other nations and specifically ensure adequate representation for Wales in standards organisations, for example NHS Digital, NHSX and INTEROpen, to align information and process models.

- we should move towards an open platform, in which data and the applications that use those data are separate and connected via defined open application programming interfaces.

- in principle, we would adopt HL7 FHIR for exchanging information relating to medications.

And we should ask:

- what can we do now that ensures rigorous evaluation and monitoring of our technology deployments, and be more open and transparent in explaining what learn in solving the problems we face in health and care information technology?

Mark