The interdependencies and relationships between standards, architecture and governance

- by Dr. Mark Wardle - 9 minutes read - 1710 wordsToday we had the June meeting of the Welsh Technical Standards Board (WTSB). One of my core aims is openness and transparency, and debating the best ways to deliver what we want to achieve.

These are my personal reflections rather than a formal opinion from WTSB. When possible, we also publish our more formal minutes.

It’s really important to me that standards are not seen as an authoritarian, centrally-controlled didactic sets of commandments sent from on-high. Instead, I see standards as enabling positive outcomes:

- enabling agile working, because standards define the technical interactions between trusted, cross-functional teams empowered to deliver their product

- enabling developer velocity, because standards permit parallel development and reduce the need for constant checks with stakeholders and other groups, because the technical contracts between teams and their products are defined by standards

- enabling loose-coupling between components and products, so that we can be strategic in our procurement and in-house development

- enabling partnerships, because we create an open platform for innovation, if we provide appropriate standards for core enterprise functionality

We discussed whether an independent standards authority would be the best way to take forward a standards-based agenda, but we came to the consensus that, standards are a force for positive culture change. We will have failed in our work if we simply issued multiple “Welsh Health Circulars” to organisations across health and care in Wales; instead, we must look how we can help support the change and outcomes to which we aspire.

Standards are an important component of the changes we need, but it is embedding an open-standards based approach that matters more than who takes the credit. If open standards become part of our routine conversations, if individuals across health and care in Wales understand and start themselves to push an open standards agenda, I take that as a success!

Of course, it’s much more difficult to measure that type of impact, than simply counting the number of mandated standards issued, but to me, cultural change is much more important, but much more difficult as well.

In my view, the best standards are pragmatic and help to solve the problems we face, ideally with easy-to-use practical implementations. To gain traction, it should be easier to adopt an open standards-based approach rather than spending time building a proprietary alternative. That means doing the hard work to make adoption easy, by providing an outstanding developer experience, for developers both inside health and care organisations in Wales, but also our partner organisations in academia and the commercial sectors. I make no apologies for such a technical and developer focus, even though our ultimate outcomes must be grounded firmly in helping to make our health and care services safer, more reliable and more efficient.

The triumvirate of standards, architecture and governance - with agility at their core

I fully expect the NHS Wales’ Architecture review to recommend a much more open and modular approach. Why? Because almost everyone I talk to within NHS Wales thinks that such an approach would be the right approach, and open up our shared services to enable greater collaboration and delivery at pace.

But what will we need to do? What should we prioritise? What modules or core building blocks do we need? And what kinds of structures do we need to support their development? What standards should we be adopting?

Standards, the architecture in which they are used and the governance structures that support both are mutually dependent and inter-related. How can we define one without the others?

My favoured approach is to consider what can be done by small cross-functional teams tasked to deliver well-defined and scoped modular building blocks, with a credible and cohesive set of shared principles underpinning all.

Each module therefore acts as a discrete abstract data or computing service, with interactions between those modules defined explicitly by a set of contracts. Contracts such as these need to cover technical matters, defining how to interact at a technical level with the underlying service, by documenting the application programming interfaces (API), but those must be supplemented by a range of legal and regulatory contracts defining how those services may be used and for what purposes. In addition, those contracts can define how the different teams might work with one another and provide assurances regarding performance and reliability. In essence, the contracts document obligations for all parties.

So what should our architectural building blocks comprise?

Technical architectural layers vs bounded context defined by our domain

It’s possible to modularise according to architectural layer or domain context.

I’m a big fan of a cleanly separated layered architecture, as a core design principle, ensuring that software code for user-facing components is separate from layers for business logic, data and its models and storage. This improves maintainability:

It’s biggest advantage (for me) is that it allows me to reduce the scope of my attention by allowing me to think about the three topics relatively independently. When I’m working on domain logic code I can mostly ignore the UI and treat any interaction with data sources as an abstract set of functions that give me the data I need and update it as I wish. When I’m working on the data access layer I focus on the details of wrangling the data into the form required by my interface. When I’m working on the presentation I can focus on the UI behavior, treating any data to display or update as magically appearing by function calls. By separating these elements I narrow the scope of my thinking in each piece, which makes it easier for me to follow what I need to do.

by Martin Fowler, blog post, 26 August 2015

When we talk about layered architecture, it is easy to imagine each layer as a horizontal strip in a large architectural diagram.

But is that all we need to consider? And at what scale does such a layered approach apply? At the application level? At a ‘whole-system’ level? At our enterprise architectural level?

For example, one suggestion from our discussions today was that that we should start to think of standards in terms of workstreams aligned to these layers within the architecture - such as “integration”, “data” and “infrastructure”. But does that imply that the same technical standards apply to all of our business domains? Are business domains such as demographics, or document management, the same?

Well yes and no. There are some core principles and core standards that surely should apply across teams, but isn’t our priority to empower our teams to make the right decisions for them?

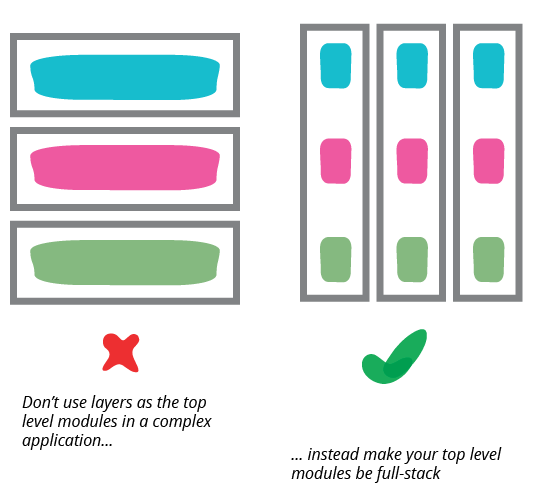

In essence, you can’t use layers as the top-level architectural divide in your enterprise but at this highest level of abstraction, we need to think instead along business domains.

This means that we think vertically rather than horizontally, and build standalone products (services), each consisting of their own layered architecture. We modularise at boundaries defined by our domain rather than technical layer.

Image from Martin Fowler, blog post, 26 August 2015

Modularisation at domain-boundaries means that our teams, our standards and our architecture are split not at functional levels such as “infrastructure” or “analytics”, but instead split according to our understanding of health and care: our domain. Such an approach is fundamental to domain-driven design, as outlined by Eric Evans in his book “Domain-Driven Design: Tackling Complexity in the Heart of Software.”.

For example, patient identity services should be a set of core shared services across health and care in Wales. Within that domain, the complexity of managing and linking demographics is managed and therefore hidden. We do the hard work to make things simple.

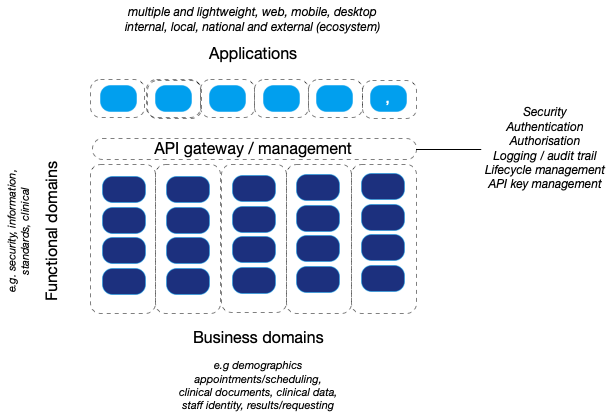

Matrix : business domains vs functional domains

The logical conclusions are:

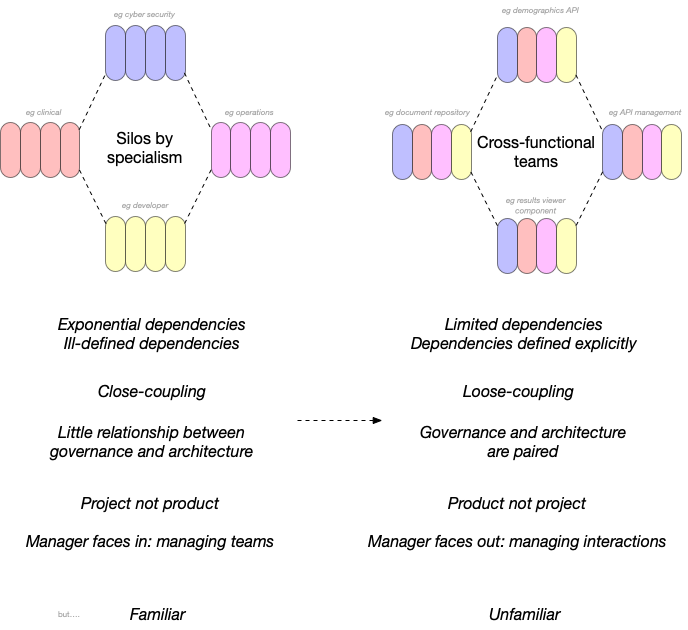

- Recognition of the value of teams that bring together complementary skills to build products

- Products that are aligned to business domains which, over time, will become ever more sophisticated. Initially, they will be fundamental products which provide an API that hides underlying legacy complexity - such as handling patient identify across multiple systems and organisations.

- Cohesiveness derived from setting top-down strategic direction and broad principles and standards, informed by specialists in functional domains (e.g. cyber security).

- Agility and pace derived from empowered teams that blend expertise in those functional domains to deliver tightly focused products that fit together because of our adoption of open standards, and themselves act as a foundation for greater innovation and sophistication.

This schematic shows how to blend different specialisms into cross-functional teams. We need to trust those teams to achieve the outcomes that we want, but tightly define those outcomes, and ensure an overall cohesive strategic approach.

And here we see multiple products, each with their own layered architecture, developed independently but cohesive, due to alignment with the greater whole; independent cogs in the wider machine.

Fractal development

Of course, one key principle is of evolution. We need to design for change - we even put change as one of our key design principles in WTSB.

What this means is that we recognise that, over time, if we do our job right, we will empower new teams to take advantage of the easy-to-use, readily available, reliable and scalable modules to create amazing solutions that hitherto have not been conceived.

In software engineering, we see a continuous march towards higher levels of abstraction. When I started, I wrote machine code, bits and bytes that directly controlled the micro-processor. I can now deploy code to a cloud provider and have it working at a global scale in seconds, and I don’t care, just like I don’t really understand how my car works, I simply turn the steering wheel and press the pedals!

If we have reliable and scalable foundational services, we can layer ever more complex logic to support our efforts to improve and transform the way we work. Just as Amazon started their work as a cloud provider by providing only simple services with well-defined APIs, they have increasingly layered on more complex services, usually at a higher level of abstraction, making use of those core foundations to build reliable, scalable services with pace.

Open technical and information standards are essential in building this layered, ever-evolving architecture, and that is why standards, architecture and governance are so mutually dependent and, why, if done right, mutually synergistic.

Mark